My name is Louis Godart and I'm a musician from Nantes - a beautiful city in the West of France. Today I am going to tell you more about the work I have been doing on Blanc as a composer and audio director.

The Music

First Notes

The first things I wrote for Blanc trace back to the spring of 2018 when we created the first prototype for the game during a game jam in Québec City. The game was called “La Piste” at that time (”The Trail” in French), and I think there is one musical track from this very early version of the game that finally made it to the final game. I already had this very clear idea that a strategic silence in the music at key times could emphasize the characters' loneliness. Silence (or at least the absence of music) needed to be a powerful tool narratively speaking, instead of forcing players into a mood of nothingness and solitude.We went through different stages of prototyping a few months after the jam. The mood of the game, the ambiance we wanted to convey, and the kind of stories we wanted to tell changed from time to time. Little by little, the tone of the game became more light-hearted, logically the musical exploration and research I did followed this same path. When it comes to writing music, I feel I am automatically attracted to nostalgia, slowness, introspection, and darkness rather than brightness and joy.

Chi va piano, va sano (?)

While searching for some musical ideas, I saw clearly in my head that the piano needed to be the core of Blanc’s soundtrack. It came from a strange thought that didn’t make it to the end, if you saw the artwork we used for the soundtrack DLC: I imagined that the cover art for it could be the black and white keys of a keyboard slowly transforming into the cub and the fawn, from left to right - a bit like in the paintings of Rob Gonsalves. It sounds kind of stupid when I explain it, but at that time it was so clear in my head that I went this direction, despite never having really composed specifically for the piano before - I am foremost a guitar player, but I always loved listening to solo piano music.

Piano is a struck-string instrument. But, as prominent as it is in western music, a major inconvenience remains: notes once played don’t sustain for long, that’s to say once you play a note, it can only fade out and disappear. The same goes for the guitar, harpsichord, harp, or any plucked or struck string instrument. I felt that in some way that could be a good metaphor for our characters’ situation: lost in the snow, their tracks bound to disappear sooner or later. Used carefully in its higher register, it may very well evoke loneliness, emptiness, and fragility.

I also went for a particular kind of piano: I didn’t want to have a classic and bright concert-hall grand piano sound with a lot of reverberation. I needed this intimacy, this feeling of being close to the instrument. That’s why I went for a virtual instrument simulating an upright piano, but in which a stripe of felt has been placed between the hammers and the strings, resulting in a softer timbre that matched the mood and the sensibility we were aiming for.

The Inspiration Corner

In terms of influences, I won’t lie: The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild was a mind-blowing experience on different levels, particularly in terms of music. It somehow combines the feelings of vastness with its open-world map with a soundtrack that is almost intimate, using piano as a key instrument. This was quite unexpected for the Zelda franchise - and it worked like a charm, giving this significant feeling of being lonely and isolated in a vast landscape.I was also very inspired by the work done by House House audio team in Untitled Goose Game and what they did in terms of music by deconstructing various Claude Debussy’s Preludes. With Blanc’s team being French and its unique art direction, going back to some early 20th-century French music would add character and charm. From that perspective, the works of Lili Boulanger (a contemporary of Debussy) were also very inspiring. She sadly passed away at 24 years old but had the time to compose a stunning catalog of very diverse and expressive music. I can only urge you to listen to some of her music if you can!

During Blanc’s production, I also discovered Eydís Evensen, an Icelandic composer whose writing moved me to tears - she uses a heavily felted piano, and the way she arranges strings really had a deep effect on my writing.

And of course, Joe Hisaishi is always somewhere in the background of my heart. Silent Love (from Takeshi Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea) is one of my favorite pieces of music ever.

Scoring the Game

With Blanc, when I first began scoring it I was determined to use piano and nothing else - already a challenge for me as primarily a guitar player. But at some point, I felt I needed something more to communicate the emotional journey of the game, without overshadowing it with something as big as a large symphonic orchestra. I decided that an intimate string orchestra should be incorporated to help push the emotions further without being too grand and epic - which would have broken the intimacy and closeness we needed.During production, I initially went for a classic way of building the game’s music: I composed concept tracks with a structure that I felt was successfully narrating the content of each level. They were basically tracks built with a beginning, a middle, and an end, and that’s what you actually can listen to in Blanc’s Soundtrack, which I wanted to sound like a suite of preludes that tell a story.

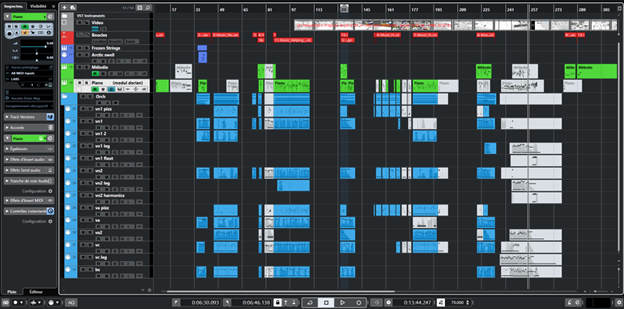

The musical composition project for the fourth level in Cubase.

What was interesting then was to de-compose each composition to make them match the different elements and events in the game. As you probably know, the biggest difference between linear audio (what you can find in movies) and video game audio is that basically anything can happen anytime in a game. For example, I had no assurance that players would trigger a cutscene or enter a certain zone at a moment in which it would be musically pertinent to transition from one part to another. My main concern was an awkward break in the course of a song that would make the transition noticeable and disturbing to the listener. Blancbeing my first game where I really embraced interactive music, I must say I came across some difficulties in this regard, but in the end, I think it turned out pretty well.

To ensure the music would be interactive, we used a middleware called FMOD. As I was no programmer, it would have been a nightmare to explain to anyone coding the game. I can imagine the conversation: “You need this part to play as a loop, but if this cutscene triggers, you have to make a transition to this other part, but only if playback reaches the end of bars 2, 4, 6 and 8, and also I would need you to crossfade the strings between the two loops, and…” Well, I think you get the point.

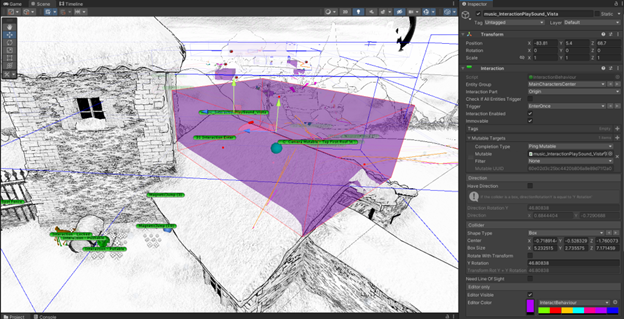

This software allowed me to freely experiment with implementation directly inside the game since the dev team also created tools in Unity so I could place triggers for the music. These were basically purple boxes that would trigger only under certain conditions (e.g.: fawn and/or wolf cub entering the box, or leaving, staying, entering once in a certain direction, etc.) to play a track or update a parameter that would allow the current music to change. That really saved us some time and back-and-forths for adjustments.

In the third level, this box triggers music when the central point between our two character’s positions enters it for the first time.

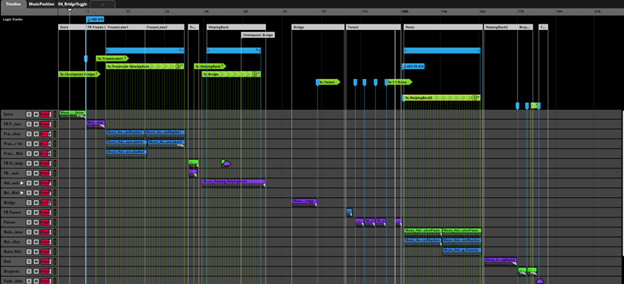

The FMOD musical event for the fourth level, with all its different tracks, regions, loops, and transitions between them.

One thing that was funny is that after composing the tracks, then de-composing them to fit the gameplay, I then had to re-compose them, and re-assemble the different sections so they can be heard in a linear form for the Soundtrack. While doing this, I had to find a balance between what I added in the music for the sake of gameplay, and what felt musically relevant to attentive listening.

Prior to Everything, There was Silence

As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, I often feel that we put too much music in movies and video games, so silence was really the starting point. My default mood while playing the game was: “let’s see what happens when nothing happens, and feel when this becomes frustrating or strange not to have any music.” Some levels are very silent, but that is something I really wanted despite it being quite counter-intuitive for a composer. With silence comes uncertainty and doubt, and that’s really what the first levels of Blanc are about.Not putting music everywhere was also a way of leaving a lot of space for sound design, to allow players to fully immerse themselves into the snow-covered world of Blanc. If you think about it, there is music in everything - we just tend to classify what is music and what is not depending on some arbitrary criteria (pitch, rhythm, harmony, etc). Pierre-Marie Blind, our Sound Designer and Foley Artist, made me want to leave even more room for his amazing work to be heard. The music and sound effects worked so well together that without the ambiance, some of the tracks put together for the Soundtrack just felt empty, and that’s why we decided to include some of his work. But I will let Pierre-Marie talk more about that.

The sound (by Pierre-Marie Blind)

Let’s set the scene:Scratch, scratch, scratch. The wolf cub's furry head just emerged from the snow.

Huff, pant.

Panting heavily, it tries to catch its breath and then lets out a faint whimper.

The cold is biting, you can even hear the frost crackling on the nearest tree branch. The wind gently whistles through nearby trees.

A gust of fine-powdered snow has brushed away the trail of the wolf’s family.

Awroooooooo.

The cub howls and the only response is the distant echo of its own voice.

It is all so quiet, yet the silence is deafening as we introduce players to the world of Blanc.

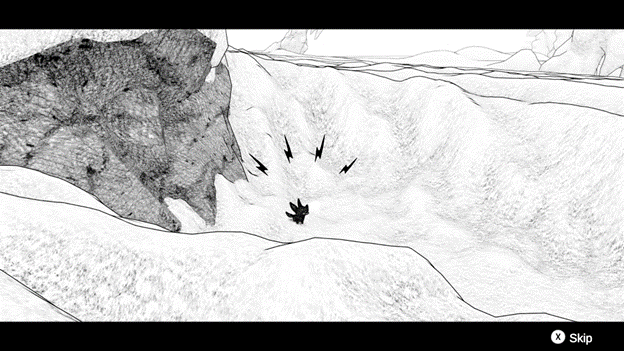

In-game screenshot, the wolf cub introduction cutscene.

So Much Snow!

Hello! My name is Pierre-Marie Blind, the Audio Designer and Foley Artist on Blanc. I remember that I was onboarded onto the project in late January 2021 - it was winter in Holland, and much to my luck it was -12 °C (32°F) and snowing heavily outside my window. I was able to get started right away.I spent my first week on the project outside gathering sounds: rolling snowballs, lifting up frozen tree trunks, shaking heavy branches, pounding on the snow, walking on frozen lakes… and falling through one of them with my microphones.

Field recording sessions for Blanc in January 2021, Venlo, The Netherlands.

Yet at this point, all I knew about the game was that the cast would be all animals. A wolf cub, a fawn, some ducks, and… plenty of snow! Just lots of it! These field recording sessions proved to be essential later and allowed all the careful articulation that was needed to bring these characters to life. Indeed the needs for Blanc's soundscape were truly one of a kind.

The Game that was Only Wind

The sound design of Blanc composes with the silence of nature during a long winter. Its reduced orchestra plays only a few instruments: the presence and movements of the animals on screen, their whines, howls, and cries of joy (hear the many celebrations in Chapter 10!). The second main instrument is the epic wilderness itself, the wind. Sometimes protective (the quiet hush of the forest in Chapter 2), sometimes lonely (the deserted village in Chapter 3, standing for a bit near those TV antennas), sometimes dangerous (have you crossed that bridge in Chapter 8?), or occasionally absent (like in Chapter 9’s eerie all-white landscape). Louis' music left plenty of room for an intricate dialogue between the arrangement of his interactive tunes and the melody of the wind.We spent a lot of time fine-tuning how we could contribute to each other’s propositions at any moment of Blanc'sadventure. Chapter 8 contains a good example: An incipient storm is coming, and our duo is now accompanied by a couple of goats as they start crossing a bridge. As they progress, the wind roars and whistles while the bridge’s metal structure screeches and whines. The music reduces itself to a reduced ostinato of violins. The danger of the environment dominates all of your senses.

A bit later, as the wolf cub and the fawn now head down alone in the snowstorm, the environment evaporates. Visibility is reduced to a few meters. Sound-wise, suddenly you can only hear the snow and wind violently whipping our duo while the music takes over the dramatic tension with dozens of instruments, high and lows, and leads the way until the scene’s ending.

“Clip-Clop”, Bringing the Characters to Life

Most of the Foley* of our two companions were done by hammering fresh snow and icy lakes with gloves and other props. As you may have noticed the wolf cub has a very different attitude compared to the fawn. He is short, easily out of breath, growls as he tries to climb the higher spots, and walks (or should I say pushes!) around the snow, a bit like a snowplow.Make sure to pause for a bit on the frozen lake in Chapter 4. You’ll start to hear the ice crackling below their feet, and who knows, they might fall through like me and my microphones!

The prop that was used for the sniffing nose of the fawn.

The pair of gloves that were used for most of the wolf cub movements across various surfaces.

For the fawn steps on the wood beams, I used cooked coconut meat and ground coffee sprinkled over a few wood planks.

The Foley for the goslings and the mother goose is a classic trick: plastic gloves and a feather duster. Their voice was made with a flute’s beak. If the goslings didn't drive you nuts by the end of Chapter 5, make sure to lean in an attentive ear once they have reached safety and you will hear them taking the cutest nap in unison!

The vocalization palette for the fawn turned out to be the most difficult design of the game. In the real world, fawns are very quiet animals, they only make a few noises, with one of the most common being a not-so-attractive “bleat.” In the final game, after many unsuccessful iterations, the fawn ended up using a mix of a few real fawn vocalizations, adult does, along with vocalizations of coyotes, human babies, baby goats, and even baby camels!

On Natural Sounds and Comical Sounds

On the technical side, Blanc’s sound design uses minimal technology and systems for real-time gameplay. We focused most of the effort on the content. Blanc being a linear experience, the most important was to get the atmosphere, the pacing, the dramatic tension, and the inherent degree of repetitiveness right.An interesting thing about repetitiveness is that some sound effects have a lot of variations and high granularity, like footsteps sounds. Others have purposefully no variations. Beyond technical considerations (like memory budget which is not really a problem on today’s platforms), the choice of having none, a bit, or many variations was conditioned by the relation the player would have to these sounds in their context. The wolf cub’s footsteps, for example, are made up of three groups: walking, trotting, and running, each broken into 2 to 3 subgroups (depending if the step is a strong support step or a light step in their animation cycle). Each of these subgroups contains up to 15 variations - he is a four-legged animal after all! Because these footsteps are triggered so often and have to feel the most natural, it was important to give them a high number of variations.

On the opposite end, a puzzle like the large tree trunk balance in Chapter 4 only has a single sound for each direction it pivots. For this, the intention was to make the riddle more amusing, so purposefully I made it feel more artificial to the ear (no natural sound repeats exactly the same in the real world), making it a bit funny and easily memorized. As our two characters balance up and down again and again until they find the solution, the sound design sets an audible running gag for each of the players’ missteps. Making sound variations is relatively cheap with today’s technology, yet the use and quantity of variations need to be carefully considered as they can make or break a subtle comical opportunity.

In-game screenshot, the tree trunk riddle in Chapter 4.

From the quietest to the most intense sequences, we hope you enjoyed the sound experience we crafted for Blanc as much as we enjoyed making it!

Buy the Soundtrack on Steam!

Follow Louis Godart on Twitter

Follow Pierre-Marie Blind on Twitter

*Foley is the art of performing custom sounds to a picture, a game, a radio, or theatre screenplay generally with the help of various props. Things like character movements are often best recorded fresh for every project to match best their attitude, weight, and other unique traits.

Changed depots in quality-assurance-2 branch